I have had many exciting experiences related to birds during my days in the field. The one that comes to my mind was during my field work in Patna, when I saw a bird that is commonly seen in South India but is very rare to sight in Patna. It was just after winter when one fine morning, my friends and I decided to go bird watching as usual and they suggested we visit the Patna University campus. I was eager for a change of scenery, as I had been bird watching in the crowded city areas for days and the campus promised a chance to see some less common birds. As we entered the campus, we began looking for birds and reached a tree patch at the corner of the boys’ hostel. There I saw the flashing red colour in the cover of the leaves. I was unsure whether it was the bird which I thought it was. I climbed onto a wall for a better view. To my delight, it was indeed the Red-whiskered Bulbul. After all those days, it was the first time I was seeing a Red-whiskered Bulbul in Patna. I could not express my excitement when I saw the reddish whiskers on its white cheeks. I was reminded of home. How ironic it is that a common bird elsewhere can bring you the happiest of feelings. Perhaps the birds can transcend the barrier of space and time! Even though we saw many colourful and a few rare birds that day, nothing could reach the peak of my excitement like the bulbul’s crest.

This is how my love for birds and nature took shape..

I grew up in a village in the Palakkad district of Kerala, surrounded by hills and a river. Although we encountered many birds and butterflies during our childhood, they were such a natural part of our daily life that we never had to give them any special place. Consequently, the question of ‘first getting interested in birds’ seems almost rhetorical. I grew up having a childhood where we climbed trees in the mango season and had to fight with birds and squirrels for ripe mangoes; where we saw barbets stealing guavas which we would be eagerly waiting for to ripen, where our mothers kept leftovers outside for birds, cats, dogs and squirrels. We caught fish in our towels from the nearby stream and collected wildflowers to create Onam floral patterns called “Pookalam”. In essence, it was ‘the growing up’ in such an environment that made me interested in birds and nature.

Morning walk during a winter morning in my village in Palakkad.

Morning walk during a winter morning in my village in Palakkad.

I completed my undergraduate degree in Zoology at Government Victoria College, Palakkad. During this time, I actively participated in butterfly censuses and nature camps. Until then, I did not care to understand the names that were given to these butterflies. However, as I participated in more of these exciting programs, butterfly watching and sometimes bird watching, I realized that documentation of biodiversity has practical applications beyond mere knowledge enrichment. The Dhoni forest in Palakkad was my frequent retreat where I would often go just to listen to the birds and watch them. During my Master’s degree in Zoology from the University of Madras, Chennai, I had the opportunity to participate in the documentation of insects in the mangrove forests of Pulicat Lake in Tamil Nadu. This was part of an NGO focused on mangrove conservation and supporting the livelihood of the people.

I remember this one time we went for a camp in Anakkampoyil, Malappuram, where we surveyed the forest and river area for butterflies and birds. The region was proposed for a pipeline project. We stayed in the area, and realised how beautiful and pristine the forest accommodating us was. We also prepared a biodiversity document of the area and submitted it to the authorities to provide as a document proof that the area is biodiversity rich and the proposed water pipeline project could adversely affect the delicate biodiversity of the area. Understanding how birds, or for that matter any living beings, interact with other components of nature intrigued me more. Understanding how species evolved to adapt with its surroundings gave me inspiration to pursue the same as a career later.

Bird survey in the Anakkampoyil area of Malappuram district.

Bird survey in the Anakkampoyil area of Malappuram district.

With a specialization in insect immunology from my Master’s dissertation and a passion for cancer biology, I was preparing for a career in that field. I had secured DST inspire and UGC JRF fellowship, and I was planning to join PhD in oncology. However, everything changed in 2019 when I spent three months in the Nelliyampathy forest range in Palakkad as part of a project funded by the Kerala State Biodiversity Board. Working as a Project Fellow, I documented biodiversity loss in areas affected by the 2018 Kerala floods and landslides within the Nelliyampathy Forest Range. This provided a new insight for me into ecology and biodiversity research, emphasizing the need for greater awareness of biodiversity loss, the lack of sufficient attention to how species change and adapt to environmental changes, and the resulting impacts on human society. Moreover, it became clear that bringing science to public platforms, where it can be easily understood by the general public, is more crucial than ever.

I joined Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History (SACON), Coimbatore in December 2020 as part of a research project addressing the issue of bird and wildlife strikes to aircrafts in Indian civil airfields from an ecological perspective and developing mitigation measures to reduce bird collision. Led by Dr. P. Pramod and Dr. P.V. Karunakaran, the project studies several civil airfields across the country. We investigate the type of birds present in and around the airfield, identify those frequently involved in bird strikes, and understand the factors that attract these birds to the airfield environment as well as to the landscape. We have developed airfield-specific mitigation measures through ecological management taking into account habitat modification, vegetation management, resource protection, stakeholder involvement and public awareness.

A Black Kite soaring in the foreground while an aircraft ascends into the distance

A Black Kite soaring in the foreground while an aircraft ascends into the distance

My interest in birds grew during my initial days in SACON. I volunteered for nature walks and took students and adults alike through the nature trail in the campus as part of the nature education program at SACON. I started learning more and more about the things around us and realized how beautiful and at the same time mysterious each living being is. Gradually, going birdwatching around campus and its nearby areas became a daily routine. The lush green forest of Anaikatty where the institute is located has inspired many researchers like me to continue their interests in understanding nature and even pursue a career in the same.

Bird watching and nature trail session at SACON organized for college students of Coimbatore.

Bird watching and nature trail session at SACON organized for college students of Coimbatore.

I am currently pursuing my PhD at SACON under the supervision of Dr. P. Pramod. My research aims to understand Indian urban birds and the factors influencing their community structure in cities. I investigate how cities provide resources for certain birds to thrive while certain other species tend to avoid urban spaces. Additionally, I am exploring how knowledge of the avian community can be applied to develop ideal cityscapes where biodiversity is considered a key component for improving the quality of life for all sections and classes of urban society. I am also involved with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) where I work with Dr. Vijesh Krishna on developing methodologies to assess the ecological impact of unsustainable residue management on biodiversity, including birds and insects.

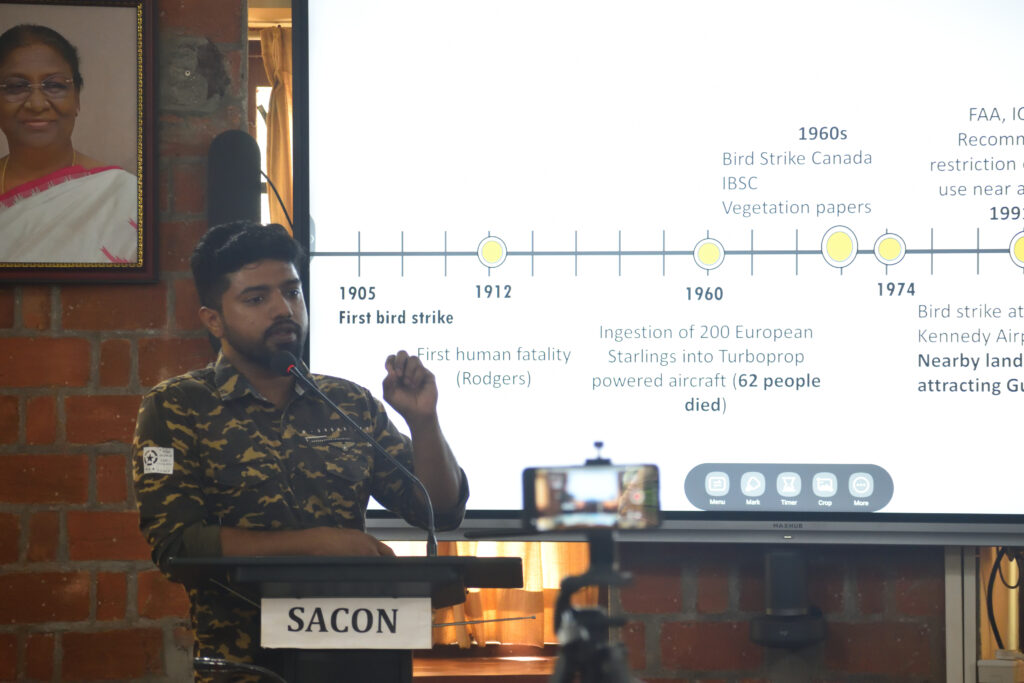

A session on the history of bird strikes during the national training program on bird hazard management for Indian Air Force officials organized at SACON.

A session on the history of bird strikes during the national training program on bird hazard management for Indian Air Force officials organized at SACON.

I love what I do because…

Since I am a part of two applied ornithology research (Bird Aircraft Strike Hazard Management and ecological impact of agricultural practices), I get to work in an environment where only a handful of researchers in the country are working. Moreover, the studies focus on immediate application of the knowledge on birds and other wildlife. My work addresses issues of national significance and contributes to developing recommendations that can help frame future policies. Since this is an area of applied ornithology and requires expertise from various fields and involvement of different stakeholders, this provides an opportunity to develop a broad range of skills and experiences.

Additionally, I am working on synanthropic (animals living in urban areas) as well as other birds that inhabit the urban jungles. This research offers me a chance to understand how birds are adapting to rapidly changing human modified habitats. It is like studying evolution in the town, but at a much shorter, faster pace.

Black Kites resting on light poles near a dumping area in Patna, Bihar

Black Kites resting on light poles near a dumping area in Patna, Bihar

Challenges I faced..

Observing and understanding birds in cities comes with its own challenges. On one occasion, a group of people confronted me as I was wandering through their neighbourhood with a camera and binoculars. They took my equipment and I had to plead with them to return it and let me go. Bird watching in urban areas can often be troublesome. Using binoculars can be tricky as people might mistake you for a spy or think you are watching them. Moreover, urban areas change rapidly over time. An open land once can be a construction site the next time you visit. This changes the entire habitat. As the habitat is changed for anthropogenic purposes (which is very drastic), the birds and other organisms in those areas will have to adapt, or in some cases, may even disappear locally.

My advice to young researchers is..

One piece of advice which I would emphasise on is that ornithology, or for that matter the study of any taxa, inevitably leads to conservation of species and habitats. Conservation biology cannot be fully understood without considering the role of humans. The influence of people on ecosystems and habitats, and the resulting impact on biodiversity depends on the extent and severity of the human intervention. This influence is often shaped by factors such as class, caste, political power, gender privilege, education, or the intersection of these societal elements. For example, the ecological footprint of a rich person or a multinational company is far greater than that of a common person or a small scale business owner.

Everything is connected; A Blue-tailed Bee-eater perches on the sandbank, feeding on an insect while cattle graze on the lush green grass, indifferent to the humans walking nearby- all under the watchful flow of the distant Ganges.

Everything is connected; A Blue-tailed Bee-eater perches on the sandbank, feeding on an insect while cattle graze on the lush green grass, indifferent to the humans walking nearby- all under the watchful flow of the distant Ganges.

Therefore, including these societal factors in your research is as important as considering anthropogenic effects on birds. Moreover, although a romanticized view of nature may have brought us into this field, it is crucial to recognize that nature cannot always be seen through this lens. As researchers, we must strike a balance between species conservation and safeguarding the basic rights of indigenous and affected communities when it comes to informed decision making and forming opinions.

ASHIQ PP

[email protected]

Research Scholar, SACON

LinkedIn profile

ResearchGate profile

It’s so nice to read. Good writing

Ashiq…

Really good